Perfect Doesn’t Mean Effective

Rapid testing is not something that comes naturally to me. As an engineer and a creator, I often find myself driven by the pursuit of perfection. In my spare time I spend days and weeks on woodworking or home improvement projects as I hone my skills and improve the quality of my work. In fact, I’d guess that just about everyone has a skill or interest they want to learn and work hard to improve upon. Likewise, I’d guess that most people view the pursuit of greater skill and higher quality output as the path to success. For the most part I would agree with them.

It may then surprise you that one of the most powerful strategies in business is to NOT pursue perfection.

Examples of this strategy are evident everywhere in the business world. New services often launch with messy, unintuitive signup processes. B2B applications rarely end up with clean, visually appealing interfaces. More and more products are releasing in “generations” rather than perfectly finished designs. In fact, while writing this article I prepared ramen with instructions to “ignore the indicated fill line” rather than the manufacturer simply providing a bowl with a correct fill line.

80% of Consequences Come From 20% of Causes

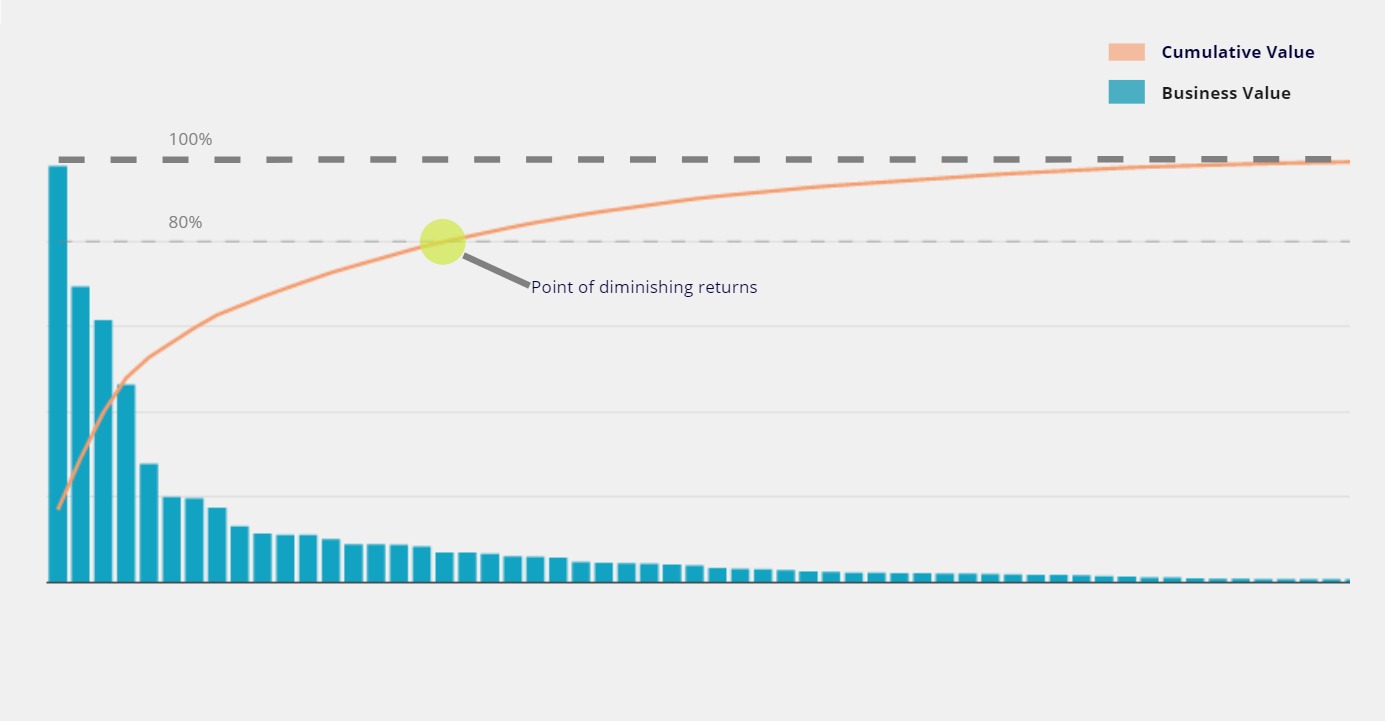

To understand why, we first need to understand the Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20. First proposed by management consultant Joseph M. Juran, the 80/20 Rule states: for many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of the causes. While originally used in the context of quality control, the principle has been successfully observed in many practices. In fundraising, 80% of the funds raised typically come from 20% of the donors. In computing, developers can typically fix 80% of software issues by addressing the top 20% of bugs.

Speed is the Optimal Path to Success

The Difference Between Rapid Testing and Recklessness is How Much You Learn

Rapid Testing Mindset is a Powerful Strategy for Innovation

Regardless of job title, everyone is operating with an incomplete understanding of their environment. Whether we know it or not, we conduct experiments every day with every action we take. Despite this – maybe even in spite of this – many companies punish failure and expect every result to be positive, leading employees to push deeper into the low value, time-wasting activities as they attempt to be “absolutely sure” their results will be positive. Some byproducts of this risk aversion are lower creativity and lower trust between employees.

However, companies that embrace rapid testing, and the failures that come with it, create an environment suitable for innovation. When the organization’s goal becomes learning, failures no longer carry negative weight. Instead, failures are celebrated as steppingstones towards better results. This environment is critical for innovation because, by definition, innovation is the exploration of the unknown. Exploration cannot exist without risk and creativity. If perfection is expected and failure is not an option, the business will get mired by group think.